Artistic Muse

Here you’ll find a selection of artworks from different eras and locations. These artworks not only show how specific cultures incorporated the sun into their art, but also, demonstrate the continual appeal of the sun to mankind’s creative nature.

Babylonian stele depicting a king with the sun, Middle Elamite period (1500–1100 BCE). This beautiful Iranian artwork can be viewed in the Musée du Louvre:

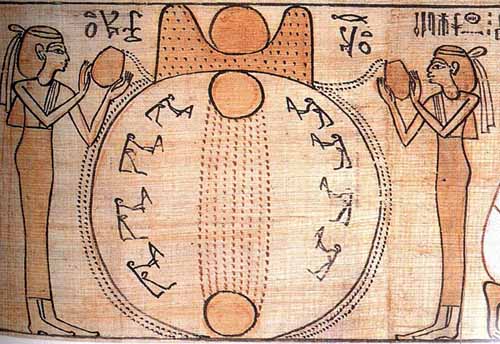

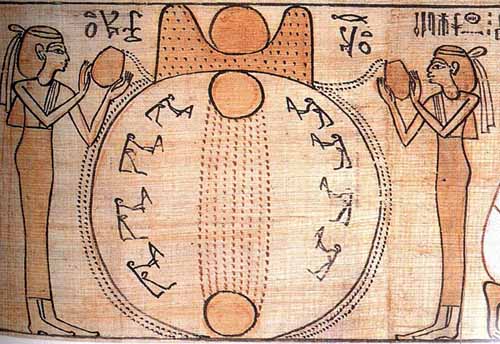

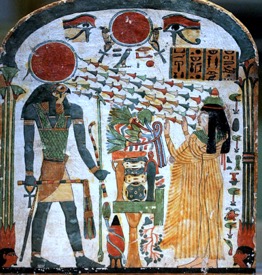

An artistic representation of the Egyptian creation myth, which stated the relationship between the sun the earth and the waters as the origin of life:

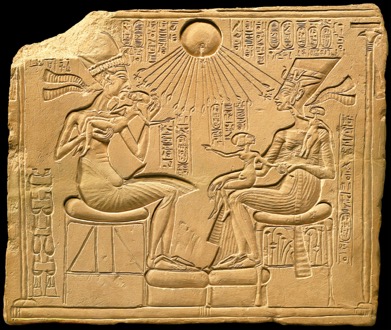

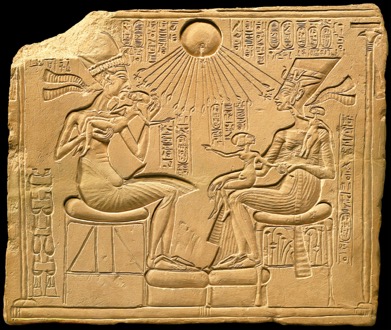

This Ancient Egyptian depiction of Akhenaten and his family worshiping the sun is dated c. 1353 – 1336 BCE[1]:

A limestone depiction of Akhenaten worshipping the sun from the amazing Amarna period. New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, (1349–1336 BCE):

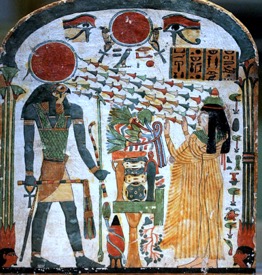

Painted wood depiction of Ra-Horakhty, a manifestation of Ra, the sun god. For more information on Ra (also called ‘Re’), read about him in the Myth and Folklore section of my website:

The Sun Stone or Aztec Calendar Stone supposedly weighs about 24 tons! Some scholars believe it was carved in the early sixteenth-century CE, but this date is not definite.

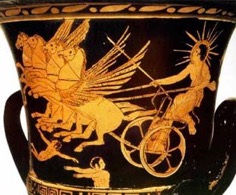

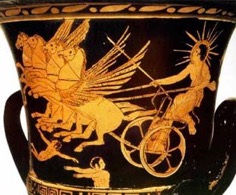

A depiction of Helios, the Greek god of the sun, on a vase dated c. 430 BCE:

Sculpted marble head of Helios, dated to the late second-century BCE:

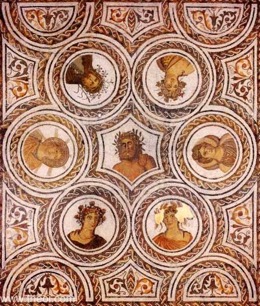

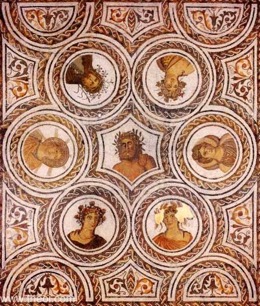

A Greek and Roman mosaic from the Imperial Roman period. On the mosaic can be seen seven portraits of figures including Helios and, his supposed counterpart, Selene (the moon):

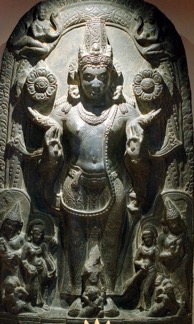

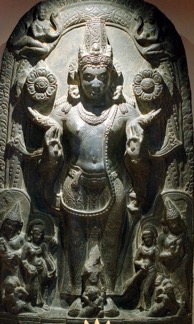

A carving of Surya, the chief Hindu solar deity. Note how Surya’s importance is emphasized through scale:

Chaco canyon (850 – 1250 CE) image of a man and sun. Scholars think the drawing was likely created by Ancient Native Americans called Anasazi in the late first-century CE:

Konark sun temple, India, is thought to have been built in 13th century CE. This wheel could be interpreted as representing the cycles of life and the sun:

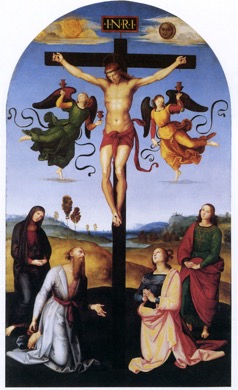

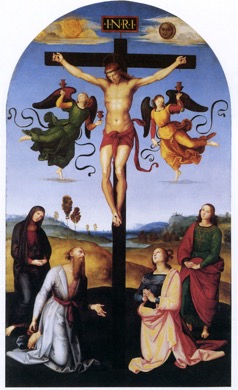

Raphael The Mond Crucifixion, c. 1503 – 03, oil on poplar. This beautiful, early work by Raphael, sees Mary and Saint John standing on both sides of the crucifix:

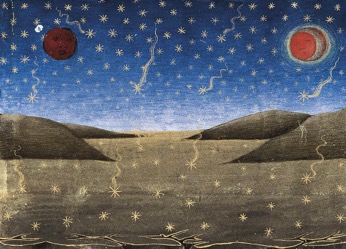

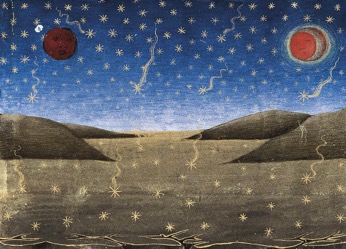

One of my favourite images of the sun is this one by Cristoforo de Predis, Death of the Sun, Moon and Stars Falling The Codex of Christoro de Predis, fifteenth-century:

The sun is a prominent feature in Japanese art, such as this 1755 piece, Phoenixes and the Rising Sun:

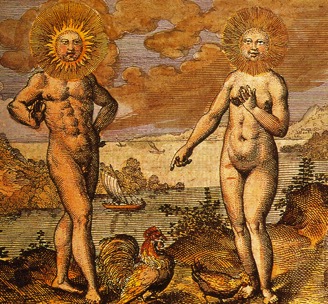

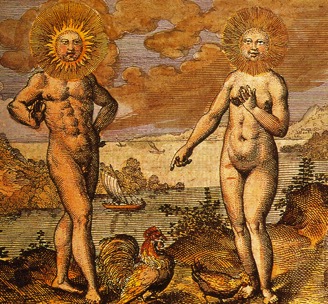

Alchemical illustrations of the sun and moon demonstrate the connection of the sun to various mental and physical states[2].

Even if the sun itself does not take up an obvious role in the artwork, the light emitted by the sun plays a constant role, particularly in natural scenes like Claude Lorrain’s lovely 1646-47 Sunrise:

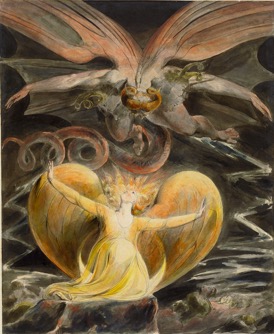

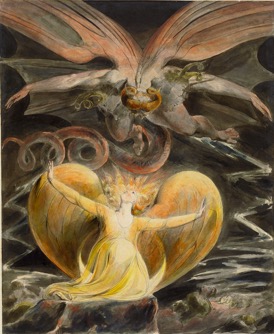

William Blake, one of The Great Red Dragon paintings, c. 1805 – 10:

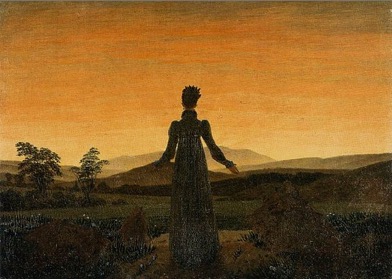

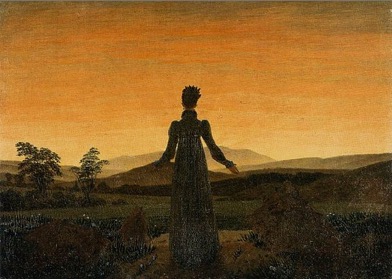

Caspar David Friedrich’s use of sunlight illuminates his painting Woman Before the Rising Sun, 1818 – 20:

And, of course, a painting from which an entire movement took its name, Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise of 1872:

Indeed, man’s interest in the sun as a fascinating visual device can even be seen in today’s culture, in images such as bp’s new logo of rays of light, the ‘Helios’ logo. The repeating pattern of the rays reminds me of the sun disk in the Ancient Babylonian Tablet of Shamash (c. 888 BCE) and that, just as the Mayan’s used synodic cycles to measure planetary movements, mankind continually looks to repetition and cyclicality to better understand the sun:

This Ancient Egyptian depiction of Akhenaten and his family worshiping the sun is dated c. 1353 – 1336 BCE[1]:

A limestone depiction of Akhenaten worshipping the sun from the amazing Amarna period. New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, reign of Akhenaten, (1349–1336 BCE):

Painted wood depiction of Ra-Horakhty, a manifestation of Ra, the sun god. For more information on Ra (also called ‘Re’), read about him in the Myth and Folklore section of my website:

The Sun Stone or Aztec Calendar Stone supposedly weighs about 24 tons! Some scholars believe it was carved in the early sixteenth-century CE, but this date is not definite.

A depiction of Helios, the Greek god of the sun, on a vase dated c. 430 BCE:

Sculpted marble head of Helios, dated to the late second-century BCE:

A Greek and Roman mosaic from the Imperial Roman period. On the mosaic can be seen seven portraits of figures including Helios and, his supposed counterpart, Selene (the moon):

A carving of Surya, the chief Hindu solar deity. Note how Surya’s importance is emphasized through scale:

Chaco canyon (850 – 1250 CE) image of a man and sun. Scholars think the drawing was likely created by Ancient Native Americans called Anasazi in the late first-century CE:

Konark sun temple, India, is thought to have been built in 13th century CE. This wheel could be interpreted as representing the cycles of life and the sun:

Raphael The Mond Crucifixion, c. 1503 – 03, oil on poplar. This beautiful, early work by Raphael, sees Mary and Saint John standing on both sides of the crucifix:

One of my favourite images of the sun is this one by Cristoforo de Predis, Death of the Sun, Moon and Stars Falling The Codex of Christoro de Predis, fifteenth-century:

The sun is a prominent feature in Japanese art, such as this 1755 piece, Phoenixes and the Rising Sun:

Alchemical illustrations of the sun and moon demonstrate the connection of the sun to various mental and physical states[2].

Even if the sun itself does not take up an obvious role in the artwork, the light emitted by the sun plays a constant role, particularly in natural scenes like Claude Lorrain’s lovely 1646-47 Sunrise:

William Blake, one of The Great Red Dragon paintings, c. 1805 – 10:

Caspar David Friedrich’s use of sunlight illuminates his painting Woman Before the Rising Sun, 1818 – 20:

And, of course, a painting from which an entire movement took its name, Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise of 1872:

Indeed, man’s interest in the sun as a fascinating visual device can even be seen in today’s culture, in images such as bp’s new logo of rays of light, the ‘Helios’ logo. The repeating pattern of the rays reminds me of the sun disk in the Ancient Babylonian Tablet of Shamash (c. 888 BCE) and that, just as the Mayan’s used synodic cycles to measure planetary movements, mankind continually looks to repetition and cyclicality to better understand the sun:

An influential essay is Evelyn Baring’s analysis of a book called Ancient Art and Ritual by Jane Harrison. I read Baring’s work at university, and wish to share with you a great essay on the subject of ancient art (particularly Greek) in relation to nature.

Earl of Evelyn Baring Cromer, Political and Literary essays, 1908-1913, chapter XXIII ‘Ancient Art and Ritual’, as published in "The Spectator," August 9, 1913, and accessed via Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/17320.

Ancient art and Ritual

Any new work written by Miss Jane Harrison is sure to be eagerly welcomed by all who take an interest in classical study or in anthropology. The conclusions at which she arrives are invariably based on profound study and assiduous research. Her generalisations are always bold, and at times strikingly original. Moreover, it is impossible for any lover of the classics, albeit he may move on a somewhat lower plane of erudition, not to sympathise with the erudite enthusiasm of an author who expresses "great delight" in discovering that Aristotle traced the origin of the Greek drama to the Dithyramb--that puzzling and "ox-driving" Dithyramb, of which Müller said that "it was vain to seek an etymology," but whose meaning has been very lucidly explained by Miss Harrison herself--and whose "heart stands still" in noting that "by a piece of luck" Plutarch gives the Dionysiac hymn which the women of Elis addressed to the "noble Bull."

It is probable that the first feeling excited in the mind of an ordinary reader, when he is asked to accept some of the conclusions at which modern students of anthropology and comparative religion have arrived, is one of scepticism. Miss Harrison is evidently alive to the existence of this feeling, for in dealing with the ritualistic significance of the Panathenaic frieze she bids her readers not to "suspect they are being juggled with," or to think that she has any wish to strain an argument with a view to "bolstering up her own art and ritual theory." It can, indeed, be no matter for surprise that such suspicions should be aroused. When, for instance, an educated man hears that the Israelites worshipped a golden calf, or that the owl and the peacock were respectively sacred to Juno and Minerva, he can readily understand what is meant. But when he is told that an Australian Emu man, strutting about in the feathers of that bird, does not think that he is imitating an Emu, but that in very fact he is an Emu, it must be admitted that his intellect, or it may be his imagination, is subjected to a somewhat severe strain. Similarly, he may at first sight find some difficulty in believing that any strict relationship can be established between the Anthesteria and Bouphonia of the cultured Athenians and the idolatrous veneration paid by the hairy and hyperborean Ainos to a sacred bear, who is at first pampered and then sacrificed, or the ritualistic tug-of-war performed by the Esquimaux, in which one side, personifying ducks, represents Summer, whilst the other, personifying ptarmigans, represents Winter. Although this scepticism is not only very natural, but even commendable, it is certain that the science of modern anthropology, in which we may reflect with legitimate pride that England has taken the lead, rests on very solid foundations. Indeed, its foundations are in some respects even better assured than those of some other sciences, such, for instance, as craniology, whose conclusions would appear at first sight to be capable of more precise demonstration, but which, in spite of this fair appearance, has as yet yielded results which are somewhat disappointing. At the birth of every science it is necessary to postulate something. The postulates that the anthropologist demands rival in simplicity those formulated by Euclid. He merely asks us to accept as facts that the main object of every living creature is to go on living, that he cannot attain this object without being supplied with food, and that, in the case of man, his supply of food must necessarily be obtained from the earth, the forest, the sea, or the river. On the basis of these elementary facts, the anthropologist then asks us to accept the conclusion that the main beliefs and acts of primitive man are intimately, and indeed almost solely, connected with his food supply; and having first, by a deductive process of reasoning, established a high degree of probability that this conclusion is correct, he proceeds to confirm its accuracy by reasoning inductively and showing that a similarity, too marked to be the result of mere accident or coincidence, exists in the practices which primitive man has adopted, throughout the world, and which can only be explained on the assumption that by methods, differing indeed in detail but substantially the same in principle, endeavours have been, and still are being, made to secure an identical object, viz. to obtain food and thus to sustain life. The various methods adopted both in the past and the present are invariably associated in one form or another with the invocation of magical influences. The primitive savage, Miss Harrison says, "is a man of action." He does not pray. He acts. If he wishes for sun or wind or rain, "he summons his tribe, and dances a sun dance or a wind dance or a rain dance." If he wants bear's flesh to eat, he does not pray to his god for strength to outwit or to master the bear, but he rehearses his hunt in a bear dance. If he notices that two things occur one after the other, his untrained intellect at once jumps to the conclusion that one is the cause and the other the effect. Thus in Australia--a specially fertile field for anthropological research, which has recently been explored with great thoroughness and intelligence by Messrs. Spencer and Gillen--the cry of the plover is frequently heard before rain falls. Therefore, when the natives wish for rain they sing a rain song in which the cry of that bird is faithfully imitated.

Before alluding to the special point which Miss Harrison deals with in _Ancient Art and Ritual_, it will be as well to glance at the views which she sets forth in her previous illuminating treatise entitled _Themis_. The former is in reality a continuation of the latter work. The view heretofore generally entertained as regards the anthropomorphic gods of Greece has been that the conception of the deity preceded the adoption of the ritual. Moreover, one school of anthropologists ably represented by Professor Ridgeway, has maintained that the phenomena of vegetation spirits, totemism, etc., rose from primary elements, notably from the belief in the existence of the soul after the death of the body. Miss Harrison and those who agree with her hold that this view involves an anthropological heresy. She deprecates the use of the word "anthropomorphic," which she describes as clumsy and too narrow. She prefers the expression ἀνθρωποφυής used by Herodotus (i. 131), signifying "of human growth." She points out that the anthropomorphism of the Greeks was preceded by theriomorphism and phytomorphism, that the ritual was "prior to the God," that so long as man was engaged in a hand-to-hand struggle for bare existence his sole care was to obtain food, and that during this stage of his existence his religious observances took almost exclusively the form of magical inducements to the earth to renew that fertility which, by the periodicity of the seasons, was at times temporarily suspended. It was only at a later period, when the struggle for existence had become less arduous, that the belief in the efficacy of magical rites decayed, and that in matters of religion the primitive Greeks "shifted from a nature-god to a human-nature god."

In her more recent work Miss Harrison reverts to this theme, and subsequently carries us one step further. She maintains that the original conception of the Greek drama was in no way spectacular. The Athenians went to the theatre as we go to church. They did not attend to see players act, but to take part in certain ritualistic things done (_dromena_). The priests of Dionysos Eleuthereus, of Apollo Daphnephoros, and of other deities attended in solemn state to assist in the performance of the rites. With that keen sense of humour which enlivens all her pages, and which made her speak in her _Themis_ of the august father of gods and men as "an automatically explosive thunderstorm," Miss Harrison says, "It is as though at His Majesty's the front row of stalls was occupied by the whole bench of bishops, with the Archbishop of Canterbury enthroned in the central stall." The actual _dromenon_ performed was of the same nature as that which in more modern times has induced villagers to make Jacks-in-the-Green and to dance round maypoles. It was always connected with the recurrence of the seasons and with the death and resurrection of vegetation. In fact, the whole ritual clustered round the idea represented at a later period in the well-known and very beautiful lines of Moschus in the _Lament for Bion_, which may be freely translated thus:

Ah me! The mallows, anise, and each flower

That withers at the blast of winter's breath

Await the vernal, renovating hour

And joyously awake from feignèd death.

The idea which impelled these ancient Greeks to perform ritualistic _dromena_ on their orchestras, which took the place of what we should call the stage, is not yet dead. Miss Harrison quotes from Mr. Lawson's work on modern Greek folklore, which is a perfect mine of knowledge on the subject of the survival of ancient religious customs in modern Greece, the story of an old woman in Euboea who was asked on Easter Eve why village society was in a state of gloom and despondency, and who replied: "Of course, I am anxious; for if Christ does not rise to-morrow, we shall have no corn this year."

It was during the fifth century that the _dromenon_ and the Dionysiac Dithyramb passed to some extent away and were merged into the drama. "Homer came to Athens, and out of Homeric stories playwrights began to make their plots." The chief agent in effecting this important change was the so-called "tyrant" Pisistratus, who was probably a free-thinker and "cared little for magic and ancestral ghosts," but who for political reasons wished to transport the Dionysia from the country to the town. "Now," Miss Harrison says, "to bring Homer to Athens was like opening the eyes of the blind." Independently of the inevitable growth of scepticism which was the natural result of increased knowledge and more acute powers of observation, it is no very hazardous conjecture to assume that the quick-witted and pleasure-loving Athenians welcomed the relief afforded to the dreary monotony of the ancient _dromena_ by the introduction of the more lively episodes drawn from the heroic sagas. "Without destroying the old, Pisistratus contrived to introduce the new, to add to the old plot of Summer and Winter the life-stories of heroes, and thereby arose the drama."

Having established her case so far, Miss Harrison makes what she herself terms "a great leap." She passes from the thing _done_, whether _dromenon_ or drama, to the thing _made_. She holds that as it was the god who arose from the rite, similarly it was the ritual connected with the worship of the god which gave birth to his representation in sculpture. Art, she says, is not, as is commonly supposed, the "handmaid of religion." "She springs straight out of the rite, and her first outward leap is the image of the god." Miss Harrison gives two examples to substantiate her contention. In the first place, she states at some length arguments of irrefutable validity to show that the Panathenaic frieze, which originally surrounded the Parthenon, represents a great ritual procession, and she adds, "Practically the whole of the reliefs that remain to us from the archaic period, and a very large proportion of those of later date, when they do not represent heroic mythology, are ritual reliefs, 'votive' reliefs, as we call them; that is, prayers or praises translated into stone."

Miss Harrison's second example is eminently calculated to give a shock to the conventional ideas generally entertained, for, as she herself says, if there is a statue in the world which apparently represents "art for art's sake" it is that of the Apollo Belvedere. Much discussion has taken place as to what Apollo is supposed to be doing in this famous statue. "There is only one answer. We do not know." Miss Harrison, however, thinks that as he is poised on tiptoe he may be in the act of taking flight from the earth. Eventually, after discussing the matter at some little length, she appears to come to the audacious conclusion which, in spite of its hardy irreverence, may very probably be true, that as Apollo was, after all, only an early Jack-in-the-Green, he has been artistically represented in marble by some sculptor of genius in that capacity.

Finally, before leaving this very interesting and instructive work, it may be noted that Miss Harrison quotes a remarkable passage from Athenaeus (xiv. 26), which certainly affords strong confirmation of her view that in the eyes of ancient authors there was an intimate connection between art and dancing, and therefore, inasmuch as dancing was ritualistic, between art and ritual. "The statues of the craftsmen of old times," Athenaeus says, "are the relics of ancient dancing."

It is greatly to be hoped that Miss Harrison will continue the study of this subject, and that she will eventually give to the world the results of her further inquiries.

[1] Akenahten and the solar monotheism he introduced is a fascinating topic. A recent book on the topic which I’m really enjoying is The Egyptian Museum in Cairo by Abeer El-Shahawy. An amazing resource for images of Egyptian art.

[2] My interest in alchemical illustrations, particularly those regarding the sun, has led me to images such as this. Perhaps my favourite alchemical image of the sun, however, is that of a green lion eating the sun, which can be seen in the 16th century text, Rosarium philosophorum, alongside 19 other intriguing woodcut images.