Myth and Folklore

Egyptian Origin Myths

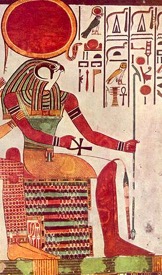

Egyptian beliefs about creation vary, but a popular version focuses on the sun rising over the circular mound of creation surrounded by the waters of chaos. It was the arrival of the sun, who was represented in the form of the god Re, which created light in darkness. The waters were composed of the eight gods of the Ogdoad, and it is these gods who represent the primeval water. It was the emergence of the sun god, the Egyptians believed, that maat (balance) was established. It is thought that this story was based on people’s experiences of the Nile flood, and the sight of mounds of earth emerging from receding streams of water.

This myth changes in its characters and story as versions developed throughout the centuries. For example, Atum (a god connected to the sun) becomes central to the myth during the Old Kingdom era. It was said that Atum emerged from the waters and from him other gods were made. More specifically, a set of nine deities called the Ennead were formed.

However, it is the sun god Re/Ra who most defines the legends of early Egyptian culture. Again, versions differ, but there are common threads which run throughout these initial Re-orientated myths. Most notable of these is the conflicts which arise between Re and other gods like Thoth and Horus. Re ages and weakens until humanity too turns against him in an episode often called “The Annihilation of Mankind” or “The Destruction of Mankind” – an episode told in The Book of the Heavenly Cow. In this story, Re finds that mankind were plotting to rebel against him, so he sends his Eye to punish the people. The Eye, though connected to Re as the Eye of Re, can also be operate as an independent female deity. At his request, she kills a large number of people until Re decides not to slay all people. To curb her killing spree, Re has beer dyed red (so as to resemble blood for the bloodthirsty goddess) which she drinks and, becoming inebriated, falls asleep. Weary of his rule over earth, Re withdraws to the sky where he begins his daily journey through the heavens to become the sun that we know of today. This event – and an example of the awe-inspiring relationship of man to sun – causes the surviving humans to be left angry at those amongst them who plotted against Re and caused his withdrawal. The ancient Egyptians pinpoint this episode as the origin of war, particularly in highlighting the importance of maat (balance) to stability of life.

Re’s withdrawal to the sky can be seen as the Egyptian attempt to understand the cylcality of the daytime. Time shifts from linear and constant (with Ra’s constant presence on earth) to repetitive and formed of episodic events. It is amazing how even as early on as ancient Egyptian culture, we can see attempts by mankind to make sense of the sun and its cyclical habits. Re is often conflated with Atum to become Re-Atum but, regardless of the deity’s name, the figure’s central role to Egypt’s perceived origins is undoubtable. What is interesting is comparisons that can be drawn with Christian ideas of genesis and Eden: with mankind upsetting their deity and, as such, being shunned to be permanently separated from their god. A god, who, in both Christian and Egyptian beliefs resides in the heavens.

Greek Myth and Worship

Ancient Roman reverence of the sun largely took the form of the worship of Helios. Helios was the personification of the sun in Greek mythology, brother to the goddesses Eos (the dawn) and Selene (the moon). It was his cyclical activity – driving the chariot of the sun across the sky each day – which was used by the Greeks to explain the sun’s repetitive movements. In Roman myth, he was equated with the god Sol.

Although Apollo is ocassionally named instead of Helios as sun god, it is important to remember the fluidity with which Greek and Roman gods evolved throughout their cultures. By Hellenistic times, the cult of Apollo had expanded and his relationship with the sun, fortified. However, Apollo was never depicted (either in art or literature) as driving the chariot of the sun across the sky, thus relating Apollo to the sun’s life-giving attributes, but reserving the actual movements of the sun and its daily effects for Helios.

Helios’s most defining story regards his son, Phaeton. Phaeton stole his father’s chariot and, when he attempted to drive it, lost control and set the earth ablaze. This myth finds a parallel in the story of Icarus. In this Greek legend, the creator of the Labyrinth, Daedalus, and his son, Icarus, attempt to flee Crete. Daedalus fashions the pair wings made of feathers and wax, but warns his son to avoid the damp of the sea or the heat of the sun – as either would prove destructive to the wings’ material. in his hubris Icarus swoops towards the sun and his wings are melted by the heat. This story carried great weight throughout the ancient world, and the allegory of ‘flying too close to the sun’ remains popular throughout history. It features, for example, in the ‘Wrack of the Apistos’, a late seventeenth-century poem I’ve included here. The sonnet recounts the story of a hugely wealthy freedman called Amotan, whose boat of treasures sunk on its way to a palace dedicated to the sun (the poem suggests he was part of a Mithraic cult) . The hugely ambitious freedman aimed too high, as the poem relates: ‘In thy name feigned to glorify / The glory of the sun / O Mithras, look'st with pity now / Upon this fearful soul / That flew too close to radiance / And thence descends so low.’

The stories of Icarus and Phaeton relate not only the follies of mankind, but the destructive capability of the sun. This, as opposed to man’s more natural perception of the sun as positive, life-giving creator harmonizes with Egyptian myths of Ra whose destruction finds embodiment in the Eye of Ra. Destructive and creative, the sun’s uncontrollable power has always fascinated mankind, playing a central role in many foundational myths of various ancient cultures.

Hindu Myth

We can also see the importance of the sun to foundational elements of Indian culture, as in the chief solar deity Surya (also called Bhanu, Ravi or Aditya). Surya is thought to be the same as Zun, who was worshipped by the afghan Zunbil dynasty.

Hindu astrology concentrates on the Navagraha, which is composed of the nine Classical planets, and of which Surya is the leader. Depictions of Surya commonly see him represented riding a chariot harnessed by seven horses, much like Helios in Greek myth. Theories differ as to what these 7 horses represent. Surya is traditionaly believed to have had three wives, names Sarayu, Prabha and Ragyi. His children with these various wives became, in themselves, central characters to Hindu legend. However, we will concentrate on Surya himself and his astrological significance.

In Vedic astrology[1], Surya is thought to represent strong, fiery attributes such as vitality, courage, kingship and strength of character. As well as being associated with certain personality traits, Surya is also connected with the following colours and materials: the gemstone ruby, the metals gold and brass, and colours including red and burgundy. He is considered the light which drives away darkness, an opposition deified in the form of Shani. It is through this duality and relationship by which Hindus would have traditionally tried to understand the changes of the sky: with people believing that certain actions having different effects depending on the time of the month the month in which they were done.

Worship of Surya can be seen in the many Surya temples of India. The most famous of these temples is the World Heritage Site of the Sun Temple in Konark, Orissa. However, there are also sun temples in Modhera, Arasavalli, Maharashtra and many other places. Many of these temples were built during the medieval period however notions of the power of the sun as deity and astronomical phenomenon can be traced back throughout Indian history.

I think it is worth giving specific, detailed examples of myths inspired by the sun, and so have copies two of my favourite examples for you to read here. Please note these myths are taken from one of my favourite educational resources: Project Gutenberg. A wonderful, accessible website for thought and learning.

Project Gutenberg eBook, Indian Fairy Tales, edited by Joseph Jacobs, Illustrated by John D. Batten and Gloria Cardew. Chapter below is ‘How Sun, Moon and Wind went out to Dinner’ and the book can be read in full at https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/7128

How the Sun, Moon and Wind went out to Dinner

One day Sun, Moon, and Wind went out to dine with their uncle and aunts Thunder and Lightning. Their mother (one of the most distant Stars you see far up in the sky) waited alone for her children's return.

Now both Sun and Wind were greedy and selfish. They enjoyed the great feast that had been prepared for them, without a thought of saving any of it to take home to their mother--but the gentle Moon did not forget her. Of every dainty dish that was brought round, she placed a small portion under one of her beautiful long finger-nails, that Star might also have a share in the treat.

On their return, their mother, who had kept watch for them all night long with her little bright eye, said, "Well, children, what have you brought home for me?" Then Sun (who was eldest) said, "I have brought nothing home for you. I went out to enjoy myself with my friends--not to fetch a dinner for my mother!" And Wind said, "Neither have I brought anything home for you, mother. You could hardly expect me to bring a collection of good things for you, when I merely went out for my own pleasure." But Moon said, "Mother, fetch a plate, see what I have brought you." And shaking her hands she showered down such a choice dinner as never was seen before.

Then Star turned to Sun and spoke thus, "Because you went out to amuse yourself with your friends, and feasted and enjoyed yourself, without any thought of your mother at home--you shall be cursed. Henceforth, your rays shall ever be hot and scorching, and shall burn all that they touch. And men shall hate you, and cover their heads when you appear."

(And that is why the Sun is so hot to this day.)

Then she turned to Wind and said, "You also who forgot your mother in the midst of your selfish pleasures--hear your doom. You shall always blow in the hot dry weather, and shall parch and shrivel all living things. And men shall detest and avoid you from this very time."

(And that is why the Wind in the hot weather is still so disagreeable.)

But to Moon she said, "Daughter, because you remembered your mother, and kept for her a share in your own enjoyment, from henceforth you shall be ever cool, and calm, and bright. No noxious glare shall accompany your pure rays, and men shall always call you 'blessed.'"

(And that is why the moon's light is so soft, and cool, and beautiful even to this day.)

The Witch and the Sun’s Sister’, Russian Fairy Tales: A Choice Collection of Muscovite Folk-lore, W. R. S. Ralston, as accessed on Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/22373

The Witch and the Sun’s Sister

In a certain far-off country there once lived a king and queen.

And they had an only son, Prince Ivan, who was dumb from

his birth. One day, when he was twelve years old, he went into

the stable to see a groom who was a great friend of his.

That groom always used to tell him tales [_skazki_], and on

this occasion Prince Ivan went to him expecting to hear some

stories [_skazochki_], but that wasn't what he heard.

"Prince Ivan!" said the groom, "your mother will soon

have a daughter, and you a sister. She will be a terrible witch,

and she will eat up her father, and her mother, and all their subjects.

So go and ask your father for the best horse he has--as

if you wanted a gallop--and then, if you want to be out of harm's

way, ride away whithersoever your eyes guide you."

Prince Ivan ran off to his father and, for the first time in his

life, began speaking to him.

At that the king was so delighted that he never thought of

asking what he wanted a good steed for, but immediately ordered

the very best horse he had in his stud to be saddled for the

prince.

Prince Ivan mounted, and rode off without caring where he

went. Long, long did he ride.

At length he came to where two old women were sewing

and he begged them to let him live with them. But they said:

"Gladly would we do so, Prince Ivan, only we have now

but a short time to live. As soon as we have broken that trunkful

of needles, and used up that trunkful of thread, that instant

will death arrive!"

Prince Ivan burst into tears and rode on. Long, long did

he ride. At length he came to where the giant Vertodub was,

and he besought him, saying:

"Take me to live with you."

"Gladly would I have taken you, Prince Ivan!" replied the

giant, "but now I have very little longer to live. As soon as I

have pulled up all these trees by the roots, instantly will come

my death!"

More bitterly still did the prince weep as he rode farther and

farther on. By-and-by he came to where the giant Vertogor

was, and made the same request to him, but he replied:

"Gladly would I have taken you, Prince Ivan! but I myself

have very little longer to live. I am set here, you know, to

level mountains. The moment I have settled matters with these

you see remaining, then will my death come!"

Prince Ivan burst into a flood of bitter tears, and rode on

still farther. Long, long did he ride. At last he came to the

dwelling of the Sun's Sister. She received him into her house,

gave him food and drink, and treated him just as if he had been

her own son.

The prince now led an easy life. But it was all no use; he

couldn't help being miserable. He longed so to know what was

going on at home.

He often went to the top of a high mountain, and thence

gazed at the palace in which he used to live, and he could see

that it was all eaten away; nothing but the bare walls remained!

Then he would sigh and weep. Once when he returned after

he had been thus looking and crying, the Sun's Sister asked

him:

"What makes your eyes so red to-day, Prince Ivan?"

"The wind has been blowing in them," said he.

The same thing happened a second time. Then the Sun's

Sister ordered the wind to stop blowing. Again a third time

did Prince Ivan come back with a blubbered face. This time

there was no help for it; he had to confess everything, and then

he took to entreating the Sun's Sister to let him go, that he

might satisfy himself about his old home. She would not let

him go, but he went on urgently entreating.

So at last he persuaded her, and she let him go away to

find out about his home. But first she provided him for the

journey with a brush, a comb, and two youth-giving apples.

However old any one might be, let him eat one of these apples,

he would grow young again in an instant.

Well, Prince Ivan came to where Vertogor was. There was

only just one mountain left! He took his brush and cast it

down on the open plain. Immediately there rose out of the

earth, goodness knows whence, high, ever so high mountains,

their peaks touching the sky. And the number of them was

such that there were more than the eye could see! Vertogor

rejoiced greatly and blithely recommenced his work.

After a time Prince Ivan came to where Vertodub was, and

found that there were only three trees remaining there. So he

took the comb and flung it on the open plain. Immediately from

somewhere or other there came a sound of trees, and forth from

the ground arose dense oak forests! each stem more huge than

the other! Vertodub was delighted, thanked the Prince, and

set to work uprooting the ancient oaks.

By-and-by Prince Ivan reached the old women, and gave

each of them an apple. They ate them, and straightway became

young again. So they gave him a handkerchief; you only had

to wave it, and behind you lay a whole lake! At last Prince

Ivan arrived at home. Out came running his sister to meet him,

caressed him fondly.

"Sit thee down, my brother!" she said, "play a tune on the

lute while I go and get dinner ready."

The Prince sat down and strummed away on the lute [_gusli_].

Then there crept a mouse out of a hole, and said to him in a

human voice:

"Save yourself, Prince. Run away quick! your sister has

gone to sharpen her teeth."

Prince Ivan fled from the room, jumped on his horse, and

galloped away back. Meantime the mouse kept running over

the strings of the lute. They twanged, and the sister never

guessed that her brother was off. When she had sharpened

her teeth she burst into the room. Lo and behold! not a soul

was there, nothing but the mouse bolting into its hole! The

witch waxed wroth, ground her teeth like anything, and set off

in pursuit.

Prince Ivan heard a loud noise and looked back. There was

his sister chasing him. So he waved his handkerchief, and a

deep lake lay behind him. While the witch was swimming across

the water, Prince Ivan got a long way ahead. But on she came

faster than ever; and now she was close at hand! Vertodub

guessed that the Prince was trying to escape from his sister.

So he began tearing up oaks and strewing them across the road.

A regular mountain did he pile up! there was no passing by for

the witch! So she set to work to clear the way. She gnawed,

and gnawed, and at length contrived by hard work to bore her

way through; but by this time Prince Ivan was far ahead.

On she dashed in pursuit, chased and chased. Just a little

more, and it would be impossible for him to escape! But Vertogor

spied the witch, laid hold of the very highest of all the mountains,

pitched it down all of a heap on the road, and flung

another mountain right on top of it. While the witch was

climbing and clambering, Prince Ivan rode and rode, and found

himself a long way ahead. At last the witch got across the

mountain, and once more set off in pursuit of her brother. By-and-by

she caught sight of him, and exclaimed:

"You sha'n't get away from me this time!" And now she is

close, now she is just going to catch him!

At that very moment Prince Ivan dashed up to the abode of

the Sun's Sister and cried:

"Sun, Sun! open the window!"

The Sun's Sister opened the window, and the Prince bounded

through it, horse and all.

Then the witch began to ask that her brother might be given

up to her for punishment. The Sun's Sister would not listen

to her, nor would she give him up. Then the witch said:

"Let Prince Ivan be weighed against me, to see which is the

heavier. If I am, then I will eat him; but if he is, then let him

kill me!"

This was done. Prince Ivan was the first to get into one of

the scales; then the witch began to get into the other. But no

sooner had she set foot in it than up shot Prince Ivan in the air,

and that with such force that he flew right up into the sky, and

into the chamber of the Sun's Sister.

But as for the Witch-Snake, she remained down below on

earth.

[The word _terem_ (plural _terema_) which occurs twice

in this story (rendered the second time by "chamber")

deserves a special notice. It is defined by Dahl, in

its antique sense, as "a raised, lofty habitation, or

part of one--a Boyar's castle--a Seigneur's house--the

dwelling-place of a ruler within a fortress," &c. The

"terem of the women," sometimes styled "of the girls,"

used to comprise the part of a Seigneur's house, on

the upper floor, set aside for the female members of

his family. Dahl compares it with the Russian

_tyurma_, a prison, and the German _Thurm_. But it

seems really to be derived from the Greek τέρεμνον,

"anything closely shut fast or closely covered, a

room, chamber," &c.

That part of the story which refers to the Cannibal

Princess is familiar to the Modern Greeks. In the

Syriote tale of "The Strigla" (Hahn, No. 65) a

princess devours her father and all his subjects. Her

brother, who had escaped while she was still a babe,

visits her and is kindly received. But while she is

sharpening her teeth with a view towards eating him, a

mouse gives him a warning which saves his life. As in

the Russian story the mouse jumps about on the strings

of a lute in order to deceive the witch, so in the

Greek it plays a fiddle. But the Greek hero does not

leave his sister's abode. After remaining concealed

one night, he again accosts her. She attempts to eat

him, but he kills her.

In a variant from Epirus (Hahn, ii. p. 283-4) the

cannibal princess is called a Chursusissa. Her brother

climbs a tree, the stem of which she gnaws almost

asunder. But before it falls, a Lamia comes to his aid

and kills his sister.

Afanasief (viii. p. 527) identifies the Sun's Sister

with the Dawn. The following explanation of the skazka

(with the exception of the words within brackets) is

given by A. de Gubernatis ("Zool. Myth." i. 183).

"Ivan is the Sun, the aurora [or dawn] is his [true]

sister; at morning, near the abode of the aurora, that

is, in the east, the shades of night [his witch, or

false sister] go underground, and the Sun arises to

the heavens; this is the mythical pair of scales. Thus

in the Christian belief, St. Michael weighs human

souls; those who weigh much sink down into hell, and

those who are light arise to the heavenly paradise."]

As an illustration of this story, Afanasief quotes a Little-Russian Skazka in which a man, who is seeking "the Isle in which there is no death," meets with various personages like those with whom the Prince at first wished to stay on his journey, and at last takes up his abode with the moon. Death comes in search of him, after a hundred years or so have elapsed, and engages in a struggle with the Moon, the result of which is that the man is caught up into the sky, and there shines thenceforth "as a star near the moon."

The Sun's Sister is a mythical being who is often mentioned in the popular poetry of the South-Slavonians. A Servian song represents a beautiful maiden, with "arms of silver up to the elbows," sitting on a silver throne which floats on water. A suitor comes to woo her. She waxes wroth and cries,

Whom wishes he to woo?

The sister of the Sun,

The cousin of the Moon,

The adopted-sister of the Dawn.

Then she flings down three golden apples, which the "marriage-proposers" attempt to catch, but "three lightnings flash from the sky" and kill the suitor and his friends.

In another Servian song a girl cries to the Sun--

O brilliant Sun! I am fairer than thou,

Than thy brother, the bright Moon,

Than thy sister, the moving star [Venus?].

In South-Slavonian poetry the sun often figures as a radiant youth. But among the Northern Slavonians, as well as the Lithuanians, the sun was regarded as a female being, the bride of the moon. "Thou askest me of what race, of what family I am," says the fair maiden of a song preserved in the Tambof Government--

My mother is--the beauteous Sun,

And my father--the bright Moon;

My brothers are--the many Stars,

And my sisters--the white Dawns.

A far more detailed account might be given of the Witch and her near relation the Baba Yaga, as well as of those masculine embodiments of that spirit of evil which is personified in them, the Snake, Koshchei, and other similar beings. But the stories which have been quoted will suffice to give at least a general idea of their moral and physical attributes. We will now turn from their forms, so constantly introduced into the skazka-drama, to some of the supernatural figures which are not so often brought upon the stage--to those mythical beings of whom (numerous as may be the traditions about them) the regular "story" does not so often speak, to such personifications of abstract ideas as are less frequently employed to set its conventional machinery in motion.

[1] Vedic astrology (traditionally called Hindu astrology) is founded upon the idea of connections between the inner and outer worlds, which can be applied to the relationship between many things. Astrology, though ancient in origin, remains an an important part of the lives of many Hindu people. For example, important dates (such as a wedding) can be influenced by the astrological happenings of that date.